The Confederacy’s Last Stand Was In East Harlem

Yonkers born-and-based artist Vinnie Bagwell has distilled all human emotions and actions into two sources: love and fear. “Ask yourself ‘Do I love it?’ or, ‘What am I afraid of?’ You can solve a lot of problems,” Bagwell said.[1]

*

On October 5, 2019, the New York City Department of Cultural Affairs co-hosted a meeting with local neighborhood organizations at the Museum of the City of New York. The gathering was one of the final stages in a process to award a million-dollar commission for a new public art work. The site, East 103rd Street and Fifth Avenue, had been vacated in 2018 after the removal of a controversial statue to a man named J. Marion Sims. New York City officials saw an opportunity, not only remove a shameful symbol, but replace it with something that represented the community.

At the beginning of the year, an open-call was posted for artists living or working in New York City to submit proposals for the million-dollar commission. Members of the East Harlem community — many of whom had been fighting to get the Sims monument removed for over a decade — gathered together in a large room at the MCNY. The long-suffering East Harlem citizens formed an audience while a seven-member selection committee — recruited by the NYC Department of Cultural Affairs — was to review the proposals of the four finalists. Three of the candidates — Simone Leigh, Tangechi Mutu, and Kehinde Wiley — are household names in the international art world. The fourth finalist, Vinnie Bagwell, is not nearly as well-known as the other candidates. Bagwell was the only candidate to present her proposal in person; along with that, she was the only native New Yorker under consideration. The crowd’s admiration for her was heard loud and clear before the committee took their vote. After over seven hours of reviewing the proposals and deliberating, the announcement from the committee finally arrived; a 4–3 vote awarding Leigh the gig over Bagwell.

Despite winning over the crowd during the presentation of her proposal, Bagwell was not able to woo the committee for a majority vote. According to conversations Bagwell had that evening, the community members were under the impression that they would get a chance to vote on the proposals along with the selection committee.[2]

Bagwell’s supporters had double the reason to be disappointed with the meeting; not only were the community members not included in the vote, but even when they made their preference clear to the committee, the votes went to the famous out-of-towner. She heard the frustration over the committee’s decision coming from the room next door and turned to those around her. “I told my design partners: ‘We’ve got to get outside and go out front because the people leaving here are going to be very upset and they won’t know what to do,’” Bagwell explained.

Video of the crowd’s response to the decision of the committee depicts a room in which no one is really in command of the situation. The disgruntled residents of the neighborhood wanted answers, but the committee’s spokespeople could manage to offer little more than a shrug. The confusion did not begin on October 5, however. Bagwell said all the details were murky from the outset. “We had no proposal guidelines, no idea of what to do. Nothing saying it had to be of a certain material, subject… I thought we should just leave nothing to the imagination.”[3]

She articulated her inspiration and intentions for the project and fielded questions from several community members. In a video of Bagwell’s presentation, the “unpolished” aspect of her artistic process is obvious. She is adamant in she has no interest in pandering to the “art-world,” but the proposal seemed specifically designed to turn-off art-scholars and critics (it included rumination on varying international spiritual beliefs, elaboration on different categories of angels, and her insistence on the importance of eternal flame bursting from the palm of her statue’s hand).

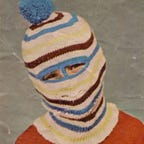

Bagwell’s proposed statue, a nine-foot-tall bronze-cast angel titled, “Victory Over Sims,” was depicted holding a staff, bare chested, and, along the body of the winged creature, faces etched to commemorate the enslaved women “forgotten and discarded by history.” She partnered with landscape architects to create a “footprint” around the area of the monument, including LED lights, a structure echoing the Vanderbilt Gate down the street, topped with a swirl of flowers.

*

During the Civil War, James Marion Sims II, born in South Carolina, was suspected by Abraham Lincoln’s administration to be traveling to Europe to raise funds for the Confederacy. After the war, Sims spent time in Montgomery, Alabama, torturing women in the name of science and medical research. After publishing his findings, he moved to New York City to further his career. In 1892, a bronze statue was cast in Munich, Germany to honor his accomplishments in the field of medicine. The bronze monument to the “father of modern gynecology” was dedicated in 1894 at what is now Bryant Park. Due to construction, the monument moved uptown in 1934.[4]

The new site chosen for the monument, the corner of East 103rd Street and Fifth Avenue, was prestigious. On the outskirts of Central Park, the statue was now situated across from the New York Academy of Medicine and the Museum of the City of New York. It was the first statue erected in the United States honoring a physician of any kind. The new location came with a new plaque as well, which described the Sims monument as a “commemoration to brilliant achievement.”[5]

*

When Vinnie Bagwell’s name was not announced as the winner of the commission, the sadness, frustration, and bitterness in the audience became audible.[6] Through gritted teeth someone shouted, “I’m so angry right now,” which pierced through the rabble of the crowd.

For years, requests from community organizations such as Beyond Sims and the Washington Street Preservation Society to remove the Sims statue had been rejected by the NYC Parks and Recreation Department, whose officials stated that “No monuments will be removed for their content.” The city had long overlooked the troublesome monument until 2017. That year, a renewed concern with the reevaluation of the origins and merits of public monuments surged across the United States. Mayor Bill de Blasio called for a report on New York City’s monuments. The report was compiled by a committee of historians, art historians, sociologists, scholars in other related fields, and city officials.

The only public fixture the report unanimously suggested the mayor remove was of J. Marion Sims. After receiving and reviewing the report, the Mayor announced that East Harlem would have one less gynecologist statue. It now rests in the same cemetery in Brooklyn where Sims himself is buried.

*

Vinnie Bagwell speaks as if she’s always got something better to say next and can’t wait to get to it. She was a saleswoman before she began making art. “Cars, clothes, mortgages,” she chuckled. Before her sales days, she studied and earned a degree in psychology. She loves both the subject of human interaction, and the souls that are behind each encounter.[7] After the meeting at the MCNY, Bagwell stood outside the museum to meet with the crestfallen attendees as they exited. “They came up and were hugging and crying and I just said, ‘If this is something you really want, go back in there and fight for it.’”[8]

*

There have been two major spikes in the construction of monuments to the Confederacy and proslavery movements in U.S. history. The first was the period was from the Reconstruction period through to the Jim Crow era. The second wave came in response to the Civil Rights movement of the 1960s and 1970s. The goal for the monuments was two-fold: reestablish traditional power structures and reform the portrayal of the Confederacy for posterity.[9] Monuments created to intimidate non-white Americans, along with the attempt to completely deny slavery as an issue in the Civil War resulted in a grassroots propaganda narrative dubbed the “Lost Cause.”

“The cult of the ‘Lost Cause’ had one goal — through monuments and other means — to rewrite the history to hide the truth,” said Mitch Landrieu in 2017, Mayor of New Orleans at the time.[10] The south in 1906 was a glimpse of what the Jim Crowe south would look like. That year, in Abbieville, South Carolina, a memorial to the Confederacy was dedicated with the inscription: “The world shall yet decide, in truth’s clear, far-off light, that the soldiers who wore the gray, and died with Lee, were in the right.” White supremacist monuments and Confederate iconography were not art; it was merely “Lost Cause” propaganda. Statues of men who fought for the perpetuation of slavery boosted morale for southerners.[11] Most southerners, even today, cannot acknowledge this history.[12]

*

Three days after the selection committee awarded Simone Leigh the commission to replace the J. Marion Sims monument, she withdrew her name from the project. She cited the community’s clear and definitive preference for Vinnie Bagwell as the cause. In her view, the community should have the art work that they want. Antwaun Sargent, one of the seven-member selection committee wrote on Twitter that Tom Finkelpearl instructed the committee members to “give the people what they want” during the deliberation.

“I really don’t mind whatever they put there,” said an employee at the Museum of the City of New York. “I haven’t thought of Sims in a year. That’s good enough for me.”[13]

*

J. Marion Sims was an abominable racist who labored for the Confederate cause, mutilated innocent women for his own gain, and was fired from his position at a New York City hospital for “illegal and potentially lethal” practice.[14] “Walking by that statue,” a member of the East Harlem community in attendance on October 5th explained, “I was reminded every day of what could have happened to me, my mother, my daughters, had we been born at a different time.” People around the neighborhood knew that statue, they knew that man. Vinnie Bagwell didn’t know about Sims until she read about the open-call in January 2019. “I mean, you don’t have to be black to walk past a statue like that and get shivers,” said a nurse who works at the nearby hospital and has lunch along Central Park. “Ask any woman how uncomfortable her annual pap smear is. And for those girls having no medicine or anything? Imagine how terrible it was then, a hundred years ago.”[15]

After seeing that statue every day, after getting swatted away like children when they complained to the city over and over, the people of East Harlem showed up to vote for their new statue. Then they weren’t even allowed to vote on their own statue. Only one of four artists deigned to attend the million-dollar vote. Perhaps Finkelpearl was right; sometimes you have to give the people what they want.

*

Monuments consecrated for the purpose of affirming a fabricated history of white supremacy and Confederate nobility billow with the black steam of fear-baked hatred. But monuments such as Vinnie Bagwell’s “Victory Over Sims” are raised up in communities in order to connect with the people in that neighborhood. For an untutored sculptor who waited forty years to start making art, Bagwell’s naiveté and lack of art-talk charmed the crowd gathered at the Museum of the City of New York. For voices, so often unheard and ignored, dispatched and disenfranchised, “Victory Over Sims” listens to them. Sometimes that’s all anyone needs.

*

[1] In phone interview with author, November 4, 2019

[2] From phone interview with author. November 4, 2019

[3] In phone interview with the author. November 4, 2019.

[4] Gonzalez, David. “An Antebellum Hero, but to Whom?” The New York Times. The New York Times, August 18, 2017. https://www.nytimes.com/2017/08/18/nyregion/j-marion-sims-statue-removal.html.

[5] Bishara, Hakim, David Carrier, R.S. Zaya, Thomas Micchelli, Harry Tafoya, Eric Vilas-Boas, and Sarah Rose Sharp. “‘We Feel Very Betrayed’: Community Protests Replacement for J. Marion Sims Monument.” Hyperallergic, October 8, 2019. https://hyperallergic.com/521269/we-feel-very-betrayed-community-protests-replacement-for-j-marion-sims-monument/.

[6] Washington Street Advisory Committee YouTube Upload — Aftermath of Announcement for Replacement of J. Marion Sims Statue

[7] In phone interview with author. November 4, 2019.

[8] In phone interview with author. November 4, 2019

[9] According to research done by the Southern Poverty Law Center, A 1929 pamphlet called A Confederate Catechism, denies that slavery or secession were causes of the Civil War. It also asserts that ‘[t]he negroes were the most spoiled domestics in the world.’

[10] “Whose Heritage? Public Symbols of the Confederacy.” Southern Poverty Law Center, February 1, 2019.

[11] “[The Lost Cause false-narrative] is the result of many decades of revisionism in the lore and even textbooks of the South that sought to create a more acceptable version of the region’s past. Confederate monuments and other symbols are very much a part of that effort.”

[12] In 1957, as the Civil Rights movement was right around the corner, Georgia state officials commissioned two “nearly identical markers” recounting “Jefferson Davis’ final days as president of the Confederate States of America.” States’ Rights was the explanation for the formation of the Confederacy in this case, not slavery. In order to fulfil the need for a noble loser, the markers explain that, at the moment when Davis was captured, “his hopes for a new nation, in which each state would exercise without interference its cherished ‘Constitutional rights,’ forever dead.”

[13] Conversation with author at Museum of the City of New York

[14] Hallman, J.C. “J. Marion Sims and the Civil War — a Rollicking Tale of Deceit and Spycraft.” The Montgomery Advertiser. Montgomery Advertiser, September 29, 2018.

[15] In conversation with unnamed community member, October 19, 2019.